Looking Critically at Our Energy Policy

Today’s the birthday of the beat poet Allen Ginsberg. According to the Writer’s Almanac, when he was 17 and in his freshman year at Columbia University, Ginsberg was introduced to Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs, whom Ginsberg later said encouraged him to think for himself and to worry less about conforming.

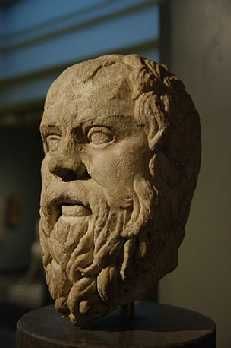

Of course, Western Culture had been flirting with non-conformist thinking since its inception (Socrates comes immediately to mind), yet I think it could be properly said that the beat poets “institutionalized” the concept, in a way, at least here in the US. Does anyone still believe that a good education is one in which millions of unanalyzed facts are stuffed into our heads?

Thinking for oneself certainly applies to the world of energy – and sustainability more generally. Today may be a good day to take a hard look at our energy paradigm, which I would summarize as follows:

Those who can afford it purchase as much energy in various forms as they wish and consume it for their pleasure and convenience. Elsewhere, a population of 1.5 billion (and growing each hour) can’t get a clean drink of water.

We often refer to our over-consumption of energy (especially in its dirtiest forms) as unsustainable, and it most certainly is that. But it’s also obscenely unfair for a small segment of our society to consume such a large portion of the planet’s scarce resources. Yes, this is an opinion (as opposed to a fact), but I think it has merit, considering that in the time it took you to read this one paragraph, several children died of starvation or the direct consequences of hunger and malnutrition.

I hope you’ll take a moment out of your day and give this concept the critical eye it deserves.

I would like to comment but somehow I see little to comment on here? I don’t know what our Energy Policy really is to start with, and pointing out starving children and preventable diseases half a world away further muddies the waters here for any meaningful comment!

Jumping off the page was the suggestion that we do not have a coherent energy policy in the USA. The ability to spend our money any way we choose trumps logic and the desire by some people to dictate how we march into the future. That is the way it is today and until the Bilderberg crowd has us moving in lockstep we will continue to see wasteful spending in the private and public sector. Brave new world IMO will have just as many Solindras and still quite a few privileged ruling class who will consume with wanton abandon.

Now if I could just make the rules, it would be a better world. We would all voluntarily cooperate and give freely to eliminate poverty and hunger. Since that is not going to happen anytime soon, I think we are better off just muddling through with a free market and scientific progress continuing to foster trickle down advancement for all. Our poor with HD TV and cell phones, electricity and flush toilets are far ahead of our most wealth ancestors just 125 years ago. L

Craig

Not one of your more cogent posts. I don’t think trusting our energy policy to the Beat poets would be a good idea, regardless of how much nonconformist thinking they could bring to bear on the issue 🙂 We’d be way better off with Aristotle.

Try as I might, I simply am unable to feel guilty about using electricity in my small rental apartment because that is somehow mysteriously contributing to folks far away not being able to have clean drinking water. I guess I am just a heartless uncaring conservative after all!!

Ha! Yeah, this one engendered a bit of ye old disagreement. I still believe, however, that we need to change our viewpoint on how energy is generated and consumed for both pragmatic and moral reasons.

Can’t argue with you there. It would be interesting to ask your readers what energy policy they would come up with if they were ‘king’ or ‘queen’, i.e., if they had the power to implement policy.

I agree that our viewpoint on energy consumption must be changed if we are going to survive as a species in the long term. But, is government intervention the way to change the hearts and minds of the consumers of energy? Look at prohibition of alcohol. See the NYT article that was published today. http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2012/06/02/whats-the-best-way-to-break-societys-bad-habits/the-paradox-of-prohibition

This is a case study that should be studied by every interventionist before embarking on a legal framework of prohibition of anything. L

People always seem to want what they are not allowed to have. Perhaps we should make alternate energy illegal.

Craig,

I can’t say I see a lot of disagreement here.

While we certainly couldn’t place Tim and his small apartment in the category of ‘rampantly excessive consumer of energy’, there are many in our nation and across the “developed” world who fit nicely in that column.

I also think the trade-off linkage is rather subtle and ill-defined between an opulent individual’s overconsumption of energy here in the US and some measure of those 1.5 billion people who try to survive without access to clean water.

That said, I do believe the linkage exists.

I also firmly believe that the relationship between over-consumption and scarcity, wherever they occur, is quite strong and rapidly growing. Our over-consumption here in the US – which is particularly potent when combined with that of the folks in China and India as they move to more closely parallel our over-consumptive lifestyle – does indeed have a disruptive effect on the planet in terms of , food prices, food production, pollution and climate, as well as on the structure and success of governments and economies globally.

As an example of one aspect of linkage, the amount we spend annually on “defense” is a direct result of our thirst for (and domestic lack of) the cheap fossil energy resources we’ve long been increasingly drawing from under the feet of foreign nations.

That necessity of “defense” is a direct result of the ill-will that our ‘expedient’ foreign policy choices have engendered over the past few generations across the oil rich world, from the Middle East and South Asia to Venezuela. Likewise, much of our foreign aid has been historically used to prop up vicious dictatorships – from the Shah of Iran, to Pinochet and Hussein – who were at least temporarily friendly to our “national interests”.

If readers will take a moment to examine list of nations with the top 15 oil reserves, they will notice two things: first, the list would serve well as a compendium of US foreign interventions over the past century, and second, we’re almost dead last on the list with just over 2% of global reserves.

The impacts of that overt and covert manipulation of foreign governments and societies – and the economic effects and biosphere effects that result – are neither insubstantial nor unforeseen. The effects of poorly regulated oil firms on the Amazon basin are staggering, and that river was once one of the biggest sources of clean fresh water on the planet.

Combine that miasma with further examples such as the global proliferation of our petroleum-intensive agriculture techniques, the influence of US-based (or US bred) multinational companies of various sorts on water resources, and the effects of the pollutants many of these industrial entities pour out into the landscape and into the air – much of which end up in water supplies.

The nature of our consumerist economy, the wastefulness that’s built into it from end to end, needs to be changed.

The folks who make decisions controlling the character of our product stream are not motivated by altruistic notions of sustainability and fairness, but by the bottom line as they see and feel it. Externalized costs like pollution and disease are not considered, except by the pressures of regulation and lawsuits. Absent more direct economic or legal incentives, this means that only the weight of paradigm shifts in society at large will sway their strategies.

Examples of this phenomenon are legion. Garment makers produced fewer coats with fox and mink when people moved vehemently away from their former appreciation for animal fur. Automakers here and abroad fitfully produced smaller cars and advertised fuel economy in response to the population’s fluctuating flirtation with frugality in the face of rising gasoline prices. Organic farmers rose to their much assailed position of prominence in reply to an increased awareness in the populace of the harmful consequences of “modern farming”.

Foreign affairs may likewise be moved – even in wartime.

The Vietnam War was not a US victory because the people of Vietnam simply would not surrender, and because the US public did not quite possess the level of cruelty sufficient to allow our military to use nuclear weapons against them. The proximity of China and involvement of the Chinese military was also a major consideration in the undeclared status of (and eventual US withdrawal from) that long and brutal conflict. Today, relations with Vietnam are finally “normalized” and the country is gradually becoming a valued US trading partner.

China herself now makes practically everything we buy (and finances a great deal of our debt). This is in no small part because the real average income of American people had stagnated from the 1970’s on, and our hunger for consumer goods could still be satisfied by cheap Chinese labor and lax environmental regulation. With astonishing speed, the former days of the Red Scare were largely forgotten. People chalk that up to the fall of the USSR, but China never fell and remains staunchly authoritarian.

I’m again reminded of a quote from Gandhi (whose great and unlooked-for achievements tie in yet another example of the power of populations) – “Whatever you do may seem insignificant to you, but it is most important that you do it.”

The power of populations is pliable, but irresistable when moving firmly in a particular direction. The combination of expectation, ingenuity, pain and vision can work wonders. Of these, only the last is still wanting.

1. Energy consumption tracks GDP; in fact, one may argue that the purpose of energy consumption is to generate wealth. If one uses the metric of GDP/Megajoule, the US compares favorably to the ROW.

2. Going back to the 1980s, there has been complaints that the US does not have an energy policy; however, we do have a defacto policy. Much of it is at the state level, but fuel efficiency standards, pollution standards, loans for nuclear power plant construction, rebates for EV purchase, DOE’s R&D portfolio, etc. are all a form of energy policy. In the US each energy policy is developed as a response to a perceived energy problem.