A World of Great Possibilities

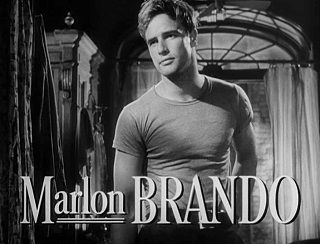

Personally, I find a relevance to this beyond simply “a good story,” as I believe we all need to revere those who change our paradigms, i.e., those who make this statement true: “The future always looks like the past—until it looks like something completely different.” I’ve always respected Brando as the man who delivered the present-day paradigm for acting, shattering that which had come before him to smithereens, much as Copernicus, Newton and Einstein had done in science.

I’m betting that you’ll find it hard to read this tale and not be overwhelmed by the sheer power of the moment.

It was on this day in 1947 that Tennessee Williams’s play A Streetcar Named Desire opened on Broadway (books by this author). He had started writing it three years earlier, during rehearsals for his first play, The Glass Menagerie (1945). When The Glass Menagerie premiered, it was a big success, and suddenly the 34-year-old playwright was famous. He was overwhelmed by all the attention and social obligations, and he left New York City, first for St. Louis and then for Mexico.

In Mexico, he continued to work on his new play. He tried out several different titles, including The Moth, Blanche’s Chair in the Moon, and The Poker Night, and finally settled on A Streetcar Named Desire. In February of 1947, he submitted the manuscript to his agent, Audrey Wood, who recommended the producer Irene Selznick. Finding a director was more difficult. Williams had his heart set on the famous Elia Kazan, but Kazan read the script and was uninterested, despite Wood and Selznick’s best persuasions. But Kazan’s wife, Molly, read the script and loved it, and finally convinced her husband to take it on. Kazan negotiated a great deal for himself: star billing and a 20 percent take of the profits. Audrey Wood wrote later that Kazan finally started to get excited during the tryouts in Boston: “[He] turned to Tennessee one night during a performance and whispered: ‘This smells like a hit!’ Further events proved that Kazan had delivered the understatement of the decade.”

Williams was so confident in Kazan’s abilities that he let him do most of the casting for the play. The only roles he wanted to help choose himself were the main characters Blanche and Stanley. Williams had heard good things about a young actress named Jessica Tandy, who was performing in his one-act play Portrait of a Madonna in Los Angeles. Williams, Wood, and Selznick traveled to Hollywood and met Kazan there, and they all went to see the one-act. They unanimously agreed to cast Tandy as Blanche.

For the role of Stanley, they decided on the rugged leading man John Garfield. But Garfield proved too difficult in negotiations. Kazan thought through the actors in his various classes, and his thoughts settled on an unknown young actor by the name of Marlon Brando. Brando had played a supporting role in a play Kazan directed called Truckline Café. The play was a failure, but the 21-year-old Brando had played his part so well that the audience would often stamp their feet and scream for a full two minutes after Brando’s big speech. Kazan decided to send Brando to Williams to see what the playwright thought of him, even though he was far younger than the character Williams had imagined. It took Kazan a while to track down Brando, who didn’t have a fixed address but slept somewhere different every night. Finally, he found the young actor, gave him $20 in bus fare, and sent him to Williams’s house at Provincetown.

A couple of days later, Kazan called Williams to ask what he thought of Brando, but Williams was confused and said that no such person had visited him. Kazan started to look for someone new. Right after that, Brando arrived in Provincetown — it had taken him three days to get there because he decided to hitchhike and save the $20 to buy food. Brando did some repair jobs on Williams’ home, fixing both the plumbing and the electricity, and then gave his reading. Williams thought it was the best thing he had ever heard. Kazan said, “I received an ecstatic call from our author, in a voice near hysteria. Brando had overwhelmed him.” They cast him as Stanley.

On opening night, Williams sent Brando a telegram: “Ride out boy and send it solid. From the greasy Polack you will someday arrive at the gloomy Dane for you have something that makes the theater a world of great possibilities.” When the curtain went down, the audience applauded for 30 minutes.

Irene Selznick said: “In those days, people stood only for the national anthem. That night was the first time I ever saw an audience get to its feet […] round after round, curtain after curtain, until Tennessee took a bow on the stage to bravos.” The play ran for more than 850 performances.