Big Ideas at the Renewable Energy Finance Forum

I enjoyed my trip to Boston earlier in the week, in which I listened to talks and spoke with the engineers at the IEEE Energy Innovation show (though they use the word “innovation” in a far different way than you or I; many of the presentations were so dry that some of their own people visibly had trouble staying awake).

But, even though I like working through the technology of renewables, I find the business practicalities far more interesting. At the end of the day, the precise photovoltaic wave form produced by a breakthrough voltage regulator doesn’t matter if large PV projects can’t get financed and remain dormant at the proposal stage.

By contrast, the Renewable Energy Finance Forum is a conference with dozens of different big ideas on which I’d like to present in a short series of posts.

The first such “big idea” is that we talked extensively about subsidies for renewables: the future of the Section 1603 cash grant, fixing the broken program of loan guarantees, and especially, carbon legislation. For instance, many of the presentations included (parenthetically) the idea that we need a pollution tax. The concept was an unaccented, glossed-over bullet on many of today’s presentations. (more…)

As I mentioned, I’m back in Boston for a couple days, attending the IEEE Energy Innovations show, and meeting a few industry colleagues who happen to be in the this part of the world. In a nutshell, the show itself has less relevance to our world than I hoped it might. The breakout sessions are extremely technical – as I suppose I would have predicted. But the main sessions are also a bit strange. Here’s an example:

As I mentioned, I’m back in Boston for a couple days, attending the IEEE Energy Innovations show, and meeting a few industry colleagues who happen to be in the this part of the world. In a nutshell, the show itself has less relevance to our world than I hoped it might. The breakout sessions are extremely technical – as I suppose I would have predicted. But the main sessions are also a bit strange. Here’s an example:

I was listening to an interview with Pulitzer-winning columnist

I was listening to an interview with Pulitzer-winning columnist

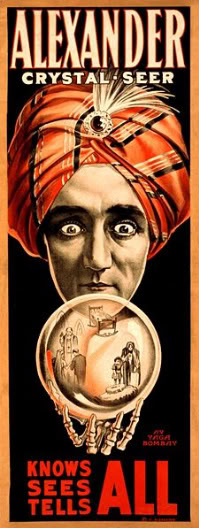

I’m one of those people who constantly tries to see into the future – not that I have any eerie talent for things like that. The future of energy and transportation, for example, is clear as a bell. Does anyone think we’re going to be driving Hummers in 40 years? Could a reasonable person believe there’ll be plenty of cheap oil in 2050 when the world population has increased 22% from today and the number of cars on the world’s roads has doubled?

I’m one of those people who constantly tries to see into the future – not that I have any eerie talent for things like that. The future of energy and transportation, for example, is clear as a bell. Does anyone think we’re going to be driving Hummers in 40 years? Could a reasonable person believe there’ll be plenty of cheap oil in 2050 when the world population has increased 22% from today and the number of cars on the world’s roads has doubled?